mirror of

https://github.com/jackyzha0/quartz.git

synced 2025-12-27 23:04:05 -06:00

Add tests for Hello function in Go

This commit is contained in:

parent

c80332db81

commit

a9b6e8cc08

@ -0,0 +1,67 @@

|

||||

|

||||

Writing tests[](#writing-tests)

|

||||

|

||||

Writing a test is just like writing a function, with a few rules

|

||||

|

||||

- It needs to be in a file with a name like `xxx_test.go`

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

- The test function must start with the word `Test`

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

- The test function takes one argument only `t *testing.T`

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

- In order to use the `*testing.T` type, you need to `import "testing"`, like we did with `fmt` in the other file

|

||||

|

||||

```go

|

||||

func TestHello(t *testing.T) {

|

||||

t.Run("saying hello to people", func(t *testing.T) {

|

||||

got := Hello("Chris")

|

||||

want := "Hello, Chris"

|

||||

assertCorrectMessage(t, got, want)

|

||||

})

|

||||

|

||||

t.Run("empty string defaults to 'world'", func(t *testing.T) {

|

||||

got := Hello("")

|

||||

want := "Hello, World"

|

||||

assertCorrectMessage(t, got, want)

|

||||

})

|

||||

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func assertCorrectMessage(t testing.TB, got, want string) {

|

||||

t.Helper()

|

||||

if got != want {

|

||||

t.Errorf("got %q want %q", got, want)

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

In your Go code, `t *testing.T` is used within your test function `TestHello` and the helper function `assertCorrectMessage` for several reasons related to writing tests in Go:

|

||||

|

||||

1. **Access to Testing Methods**: `t *testing.T` is a pointer to Go's testing framework's `T` type, which provides methods for controlling test execution and logging. By passing `t` into your test functions, you gain access to methods such as `t.Errorf`, `t.Fatalf`, `t.Run`, and `t.Helper`.

|

||||

|

||||

2. **Running Subtests**: The `t.Run` method allows you to define subtests or table-driven tests within your test function. This approach makes your tests more organized and can be useful for testing different scenarios or inputs for the same function. Each call to `t.Run` can be considered as a separate test case within the broader test function.

|

||||

|

||||

3. **Error Reporting and Logging**: The methods on `*testing.T` like `t.Errorf` are used for reporting errors. When you call `t.Errorf`, it logs the error message and marks the test as failed but continues execution. This is useful for running multiple checks within a single test and getting a report on all failures.

|

||||

|

||||

4. **Helper Function**: The `t.Helper` method in your `assertCorrectMessage` function is used to mark that function as a test helper. When this method is called, the function is skipped when reporting where an error occurred, making the error output more readable. It tells the test framework that the actual place of interest is where the helper function was called, not inside the helper function itself.

|

||||

|

||||

5. **Interface `testing.TB`**: In your `assertCorrectMessage` function, you use `testing.TB` instead of `*testing.T`. The `testing.TB` is an interface that is implemented by both `*testing.T` and `*testing.B` (where `B` is for benchmarks). Using `testing.TB` makes your helper function more flexible because it can be used with both testing and benchmarking.

|

||||

|

||||

In summary, `t *testing.T` and `testing.TB` are essential for structuring your tests, running subtests, reporting errors, and making your test code more maintainable and flexible in Go.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

For helper functions, it's a good idea to accept a `testing.TB` which is an interface that `*testing.T` and `*testing.B` both satisfy, so you can call helper functions from a test, or a benchmark (don't worry if words like "interface" mean nothing to you right now, it will be covered later).

|

||||

|

||||

`t.Helper()` is needed to tell the test suite that this method is a helper. By doing this when it fails the line number reported will be in our _function call_ rather than inside our test helper. This will help other developers track down problems easier. If you still don't understand, comment it out, make a test fail and observe the test output. Comments in Go are a great way to add additional information to your code, or in this case, a quick way to tell the compiler to ignore a line. You can comment out the `t.Helper()` code by adding two forward slashes `//` at the beginning of the line. You should see that line turn grey or change to another color than the rest of your code to indicate it's now commented out.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### Check chapter 1 [here](https://quii.gitbook.io/learn-go-with-tests/go-fundamentals/hello-world)

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

[[Property Based Testing]]

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

[[examples in golang]]

|

||||

29

content/Property Based Testing.md

Normal file

29

content/Property Based Testing.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,29 @@

|

||||

Property-based testing is a testing approach where you test the properties of your code with many random inputs, rather than specifying individual test cases with expected outputs. This technique originates from the Haskell library QuickCheck and has been adapted for various programming languages.

|

||||

|

||||

### Key Concepts of Property-Based Testing:

|

||||

|

||||

1. **Randomized Inputs**: Instead of hand-crafting specific inputs, property-based tests generate random inputs. This can uncover edge cases that manual tests might miss.

|

||||

|

||||

2. **Testing Properties**: Instead of testing for specific expected results, property-based tests verify certain properties or invariants of the code. A property is a statement like "for all inputs x, y, and z, condition C holds true".

|

||||

|

||||

3. **Automated Case Generation**: The testing framework automatically generates a wide range of inputs, including edge cases, to thoroughly test the code against the defined properties.

|

||||

|

||||

4. **Shrinking**: When a test fails, the testing framework tries to "shrink" the failing test case to the simplest possible input that still causes a failure. This makes debugging easier.

|

||||

|

||||

### Advantages:

|

||||

|

||||

- **Covers More Cases**: Random input generation can cover a broader range of inputs than manually specified test cases.

|

||||

- **Finds Edge Cases**: It's effective in finding edge cases and bugs that developers might not have thought to test.

|

||||

- **Expressive**: Properties can be more expressive and cover a broader range of scenarios than specific test cases.

|

||||

|

||||

### Disadvantages:

|

||||

|

||||

- **Complexity**: Writing good property tests can be more complex than writing traditional unit tests.

|

||||

- **Interpretation**: When a test fails, understanding why can be more challenging, especially if the failing input is complex or unintuitive.

|

||||

- **Coverage**: It's not always clear how thorough the random input generation is, or whether it covers all important cases.

|

||||

|

||||

### Example Usage:

|

||||

|

||||

In a language like Python, you might use a library like Hypothesis for property-based testing. For instance, testing a sorting function might involve the property "for any list of integers, the function should return a list with the same elements in ascending order". The testing framework would then generate random lists of integers, pass them to the function, and check if the output satisfies this property.

|

||||

|

||||

Property-based testing is particularly useful in scenarios where the input domain is large or complex and where it's challenging to think of all possible cases. However, it's generally used in conjunction with, rather than as a replacement for, traditional example-based tests.

|

||||

317

content/examples in golang.md

Normal file

317

content/examples in golang.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,317 @@

|

||||

## Introduction

|

||||

|

||||

Godoc [examples](https://go.dev/pkg/testing/#hdr-Examples) are snippets of Go code that are displayed as package documentation and that are verified by running them as tests. They can also be run by a user visiting the godoc web page for the package and clicking the associated “Run” button.

|

||||

|

||||

Having executable documentation for a package guarantees that the information will not go out of date as the API changes.

|

||||

|

||||

The standard library includes many such examples (see the [`strings` package](https://go.dev/pkg/strings/#Contains), for instance).

|

||||

|

||||

This article explains how to write your own example functions.

|

||||

|

||||

## Examples are tests

|

||||

|

||||

Examples are compiled (and optionally executed) as part of a package’s test suite.

|

||||

|

||||

As with typical tests, examples are functions that reside in a package’s `_test.go` files. Unlike normal test functions, though, example functions take no arguments and begin with the word `Example` instead of `Test`.

|

||||

|

||||

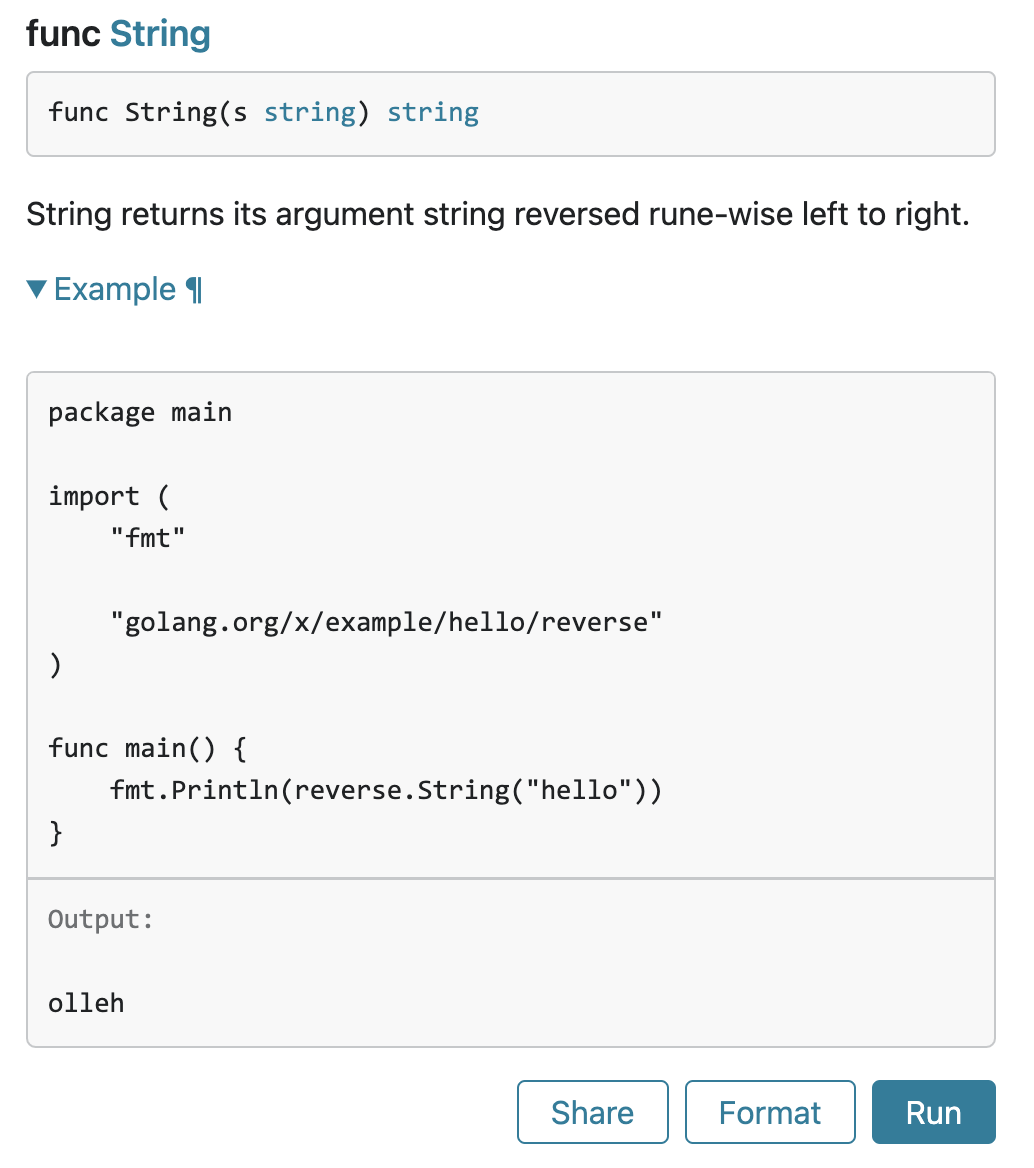

The [`reverse` package](https://pkg.go.dev/golang.org/x/example/hello/reverse/) is part of the [Go example repository](https://cs.opensource.google/go/x/example). Here’s an example that demonstrates its `String` function:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

package reverse_test

|

||||

|

||||

import (

|

||||

"fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

"golang.org/x/example/hello/reverse"

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

func ExampleString() {

|

||||

fmt.Println(reverse.String("hello"))

|

||||

// Output: olleh

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This code might live in `example_test.go` in the `reverse` directory.

|

||||

|

||||

The Go package documentation server _pkg.go.dev_ presents this example alongside the [`String` function’s documentation](https://pkg.go.dev/golang.org/x/example/hello/reverse/#String):

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Running the package’s test suite, we can see the example function is executed with no further arrangement from us:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ go test -v

|

||||

=== RUN TestString

|

||||

--- PASS: TestString (0.00s)

|

||||

=== RUN ExampleString

|

||||

--- PASS: ExampleString (0.00s)

|

||||

PASS

|

||||

ok golang.org/x/example/hello/reverse 0.209s

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Output comments

|

||||

|

||||

What does it mean that the `ExampleString` function “passes”?

|

||||

|

||||

As it executes the example, the testing framework captures data written to standard output and then compares the output against the example’s “Output:” comment. The test passes if the test’s output matches its output comment.

|

||||

|

||||

To see a failing example we can change the output comment text to something obviously incorrect

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

func ExampleString() {

|

||||

fmt.Println(reverse.String("hello"))

|

||||

// Output: golly

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

and run the tests again:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ go test

|

||||

--- FAIL: ExampleString (0.00s)

|

||||

got:

|

||||

olleh

|

||||

want:

|

||||

golly

|

||||

FAIL

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

If we remove the output comment entirely

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

func ExampleString() {

|

||||

fmt.Println(reverse.String("hello"))

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

then the example function is compiled but not executed:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ go test -v

|

||||

=== RUN TestString

|

||||

--- PASS: TestString (0.00s)

|

||||

PASSIntroduction

|

||||

Godoc examples are snippets of Go code that are displayed as package documentation and that are verified by running them as tests. They can also be run by a user visiting the godoc web page for the package and clicking the associated “Run” button.

|

||||

|

||||

Having executable documentation for a package guarantees that the information will not go out of date as the API changes.

|

||||

|

||||

The standard library includes many such examples (see the strings package, for instance).

|

||||

|

||||

This article explains how to write your own example functions.

|

||||

|

||||

Examples are tests

|

||||

Examples are compiled (and optionally executed) as part of a package’s test suite.

|

||||

|

||||

As with typical tests, examples are functions that reside in a package’s _test.go files. Unlike normal test functions, though, example functions take no arguments and begin with the word Example instead of Test.

|

||||

|

||||

The reverse package is part of the Go example repository. Here’s an example that demonstrates its String function:

|

||||

|

||||

package reverse_test

|

||||

|

||||

import (

|

||||

"fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

"golang.org/x/example/hello/reverse"

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

func ExampleString() {

|

||||

fmt.Println(reverse.String("hello"))

|

||||

// Output: olleh

|

||||

}

|

||||

This code might live in example_test.go in the reverse directory.

|

||||

|

||||

The Go package documentation server pkg.go.dev presents this example alongside the String function’s documentation:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Running the package’s test suite, we can see the example function is executed with no further arrangement from us:

|

||||

|

||||

$ go test -v

|

||||

=== RUN TestString

|

||||

--- PASS: TestString (0.00s)

|

||||

=== RUN ExampleString

|

||||

--- PASS: ExampleString (0.00s)

|

||||

PASS

|

||||

ok golang.org/x/example/hello/reverse 0.209s

|

||||

Output comments

|

||||

What does it mean that the ExampleString function “passes”?

|

||||

|

||||

As it executes the example, the testing framework captures data written to standard output and then compares the output against the example’s “Output:” comment. The test passes if the test’s output matches its output comment.

|

||||

|

||||

To see a failing example we can change the output comment text to something obviously incorrect

|

||||

|

||||

func ExampleString() {

|

||||

fmt.Println(reverse.String("hello"))

|

||||

// Output: golly

|

||||

}

|

||||

and run the tests again:

|

||||

|

||||

$ go test

|

||||

--- FAIL: ExampleString (0.00s)

|

||||

got:

|

||||

olleh

|

||||

want:

|

||||

golly

|

||||

FAIL

|

||||

If we remove the output comment entirely

|

||||

|

||||

func ExampleString() {

|

||||

fmt.Println(reverse.String("hello"))

|

||||

}

|

||||

then the example function is compiled but not executed:

|

||||

|

||||

$ go test -v

|

||||

=== RUN TestString

|

||||

--- PASS: TestString (0.00s)

|

||||

PASS

|

||||

ok golang.org/x/example/hello/reverse 0.110s

|

||||

Examples without output comments are useful for demonstrating code that cannot run as unit tests, such as that which accesses the network, while guaranteeing the example at least compiles.

|

||||

|

||||

Example function names

|

||||

Godoc uses a naming convention to associate an example function with a package-level identifier.

|

||||

|

||||

func ExampleFoo() // documents the Foo function or type

|

||||

func ExampleBar_Qux() // documents the Qux method of type Bar

|

||||

func Example() // documents the package as a whole

|

||||

Following this convention, godoc displays the ExampleString example alongside the documentation for the String function.

|

||||

|

||||

Multiple examples can be provided for a given identifier by using a suffix beginning with an underscore followed by a lowercase letter. Each of these examples documents the String function:

|

||||

|

||||

func ExampleString()

|

||||

func ExampleString_second()

|

||||

func ExampleString_third()

|

||||

Larger examples

|

||||

Sometimes we need more than just a function to write a good example.

|

||||

|

||||

For instance, to demonstrate the sort package we should show an implementation of sort.Interface. Since methods cannot be declared inside a function body, the example must include some context in addition to the example function.

|

||||

|

||||

To achieve this we can use a “whole file example.” A whole file example is a file that ends in _test.go and contains exactly one example function, no test or benchmark functions, and at least one other package-level declaration. When displaying such examples godoc will show the entire file.

|

||||

|

||||

Here is a whole file example from the sort package:

|

||||

|

||||

package sort_test

|

||||

|

||||

import (

|

||||

"fmt"

|

||||

"sort"

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

type Person struct {

|

||||

Name string

|

||||

Age int

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func (p Person) String() string {

|

||||

return fmt.Sprintf("%s: %d", p.Name, p.Age)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// ByAge implements sort.Interface for []Person based on

|

||||

// the Age field.

|

||||

type ByAge []Person

|

||||

|

||||

func (a ByAge) Len() int { return len(a) }

|

||||

func (a ByAge) Swap(i, j int) { a[i], a[j] = a[j], a[i] }

|

||||

func (a ByAge) Less(i, j int) bool { return a[i].Age < a[j].Age }

|

||||

|

||||

func Example() {

|

||||

people := []Person{

|

||||

{"Bob", 31},

|

||||

{"John", 42},

|

||||

{"Michael", 17},

|

||||

{"Jenny", 26},

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println(people)

|

||||

sort.Sort(ByAge(people))

|

||||

fmt.Println(people)

|

||||

|

||||

// Output:

|

||||

// [Bob: 31 John: 42 Michael: 17 Jenny: 26]

|

||||

// [Michael: 17 Jenny: 26 Bob: 31 John: 42]

|

||||

}

|

||||

A package can contain multiple whole file examples; one example per file. Take a look at the sort package’s source code to see this in practice.

|

||||

|

||||

Conclusion

|

||||

Godoc examples are a great way to write and maintain code as documentation. They also present editable, working, runnable examples your users can build on. Use them!

|

||||

ok golang.org/x/example/hello/reverse 0.110s

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Examples without output comments are useful for demonstrating code that cannot run as unit tests, such as that which accesses the network, while guaranteeing the example at least compiles.

|

||||

|

||||

## Example function names

|

||||

|

||||

Godoc uses a naming convention to associate an example function with a package-level identifier.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

func ExampleFoo() // documents the Foo function or type

|

||||

func ExampleBar_Qux() // documents the Qux method of type Bar

|

||||

func Example() // documents the package as a whole

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Following this convention, godoc displays the `ExampleString` example alongside the documentation for the `String` function.

|

||||

|

||||

Multiple examples can be provided for a given identifier by using a suffix beginning with an underscore followed by a lowercase letter. Each of these examples documents the `String` function:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

func ExampleString()

|

||||

func ExampleString_second()

|

||||

func ExampleString_third()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

## Larger examples

|

||||

|

||||

Sometimes we need more than just a function to write a good example.

|

||||

|

||||

For instance, to demonstrate the [`sort` package](https://go.dev/pkg/sort/) we should show an implementation of `sort.Interface`. Since methods cannot be declared inside a function body, the example must include some context in addition to the example function.

|

||||

|

||||

To achieve this we can use a “whole file example.” A whole file example is a file that ends in `_test.go` and contains exactly one example function, no test or benchmark functions, and at least one other package-level declaration. When displaying such examples godoc will show the entire file.

|

||||

|

||||

Here is a whole file example from the `sort` package:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

package sort_test

|

||||

|

||||

import (

|

||||

"fmt"

|

||||

"sort"

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

type Person struct {

|

||||

Name string

|

||||

Age int

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func (p Person) String() string {

|

||||

return fmt.Sprintf("%s: %d", p.Name, p.Age)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

// ByAge implements sort.Interface for []Person based on

|

||||

// the Age field.

|

||||

type ByAge []Person

|

||||

|

||||

func (a ByAge) Len() int { return len(a) }

|

||||

func (a ByAge) Swap(i, j int) { a[i], a[j] = a[j], a[i] }

|

||||

func (a ByAge) Less(i, j int) bool { return a[i].Age < a[j].Age }

|

||||

|

||||

func Example() {

|

||||

people := []Person{

|

||||

{"Bob", 31},

|

||||

{"John", 42},

|

||||

{"Michael", 17},

|

||||

{"Jenny", 26},

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

fmt.Println(people)

|

||||

sort.Sort(ByAge(people))

|

||||

fmt.Println(people)

|

||||

|

||||

// Output:

|

||||

// [Bob: 31 John: 42 Michael: 17 Jenny: 26]

|

||||

// [Michael: 17 Jenny: 26 Bob: 31 John: 42]

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

A package can contain multiple whole file examples; one example per file. Take a look at the [`sort` package’s source code](https://go.dev/src/sort/) to see this in practice.

|

||||

|

||||

## Conclusion

|

||||

|

||||

Godoc examples are a great way to write and maintain code as documentation. They also present editable, working, runnable examples your users can build on. Use them!

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user